Have you ever told multiple stories to explain or expand upon a point? Maybe you were telling your friend how much of a blessing your parents were. You started with a story about how they came to all of your football games as a kid. And then you told a story about some time they helped you with some big expenditure, like a car or college tuition. Then you finished with a story about how they gave you invaluable advice, just at the right time. Maybe it was relationship or career advice – whatever it was, it helped to set the trajectory for the rest of your life. The point of all of these stories was that your parents were good parents, but each story shed a different light on how that was so. The story about your childhood sports showed how they sacrificed their time for you. The story about the financial help showed how they sacrificed their money for you. The story about the good advice showed that they cared enough about you to speak into your life from all the wisdom they gained throughout theirs. Each story had the same overarching point, but each story’s details revealed something a little different. Jesus occasionally used this technique when he was telling parables.

There are a number of times when Jesus tells multiple parables with the same basic point. Yet each parable sheds new light on the subject he is speaking about. The first example of this is probably very familiar to you, because two of the three parables are quite famous. Luke 15 contains three related parables: the Parable of the Lost Sheep (Luke 15:3-7), the Parable of the Lost Drachma (Luke 15:8-10), and the Parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11-32). All of these parables are told one after another and share the same context (Luke 15:1-2). Jesus had been spending time with sinners and tax collectors (the irreligious), and this bothered the Pharisees and scribes (the ultrareligious). Jesus tells these three parables because of the grumblings of the scribes and Pharisees. So, each parable ultimately serves the purpose of explaining why Jesus would receive sinners and eat with them (Luke 15:2).

When reading each parable, one should also notice some obvious similarities. Each parable tells of something or someone that was lost (Luke 15:4, 8, 24, 32), and which was then found (Luke 15:5, 9, 24, 32), resulting in a great celebration (Luke 15:6, 9, 22-23, 25). Jesus tells us that the lost sheep/coin/son that was found represents a sinner who has repented resulting in a great celebration in heaven (Luke 15:7, 10). The point Jesus is getting at is that it is right and good for him to pursue relationships with the tax collectors and sinners because they clearly need to repent, and God loves it when sinners repent. As for the scribes and Pharisees, they had forgotten that God loves when sinners repent, which means these parables are correcting them (see Luke 15:25-32).

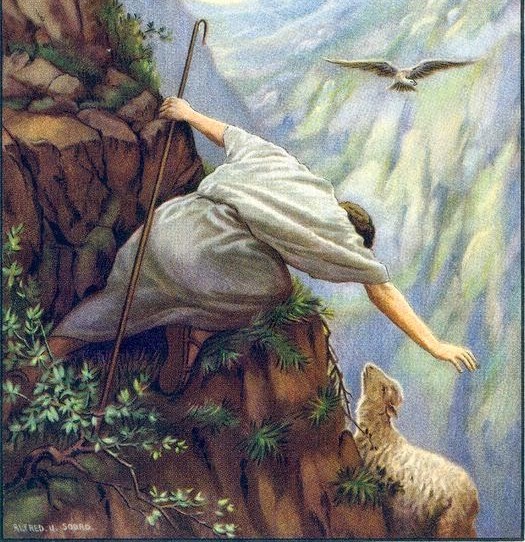

As easy as it is to see the connection between the three parables in Luke 15, these parables are not always taught together. Sometimes, we just hear about the Parable of the Prodigal Son. But this parable needs the others to stay grounded. In both The Lost Drachma and The Lost Sheep, Jesus tells us that the coin and the sheep were pursued and found by their owners. The sheep did not wander back into the fold all on its own, and the coin did not return to the money bag on its own. Jesus goes so far as to point out that the shepherd left the ninety-nine to find the one, and that the woman carefully cleaned the whole house at night just to find the lost drachma. These are important points for a few reasons. In context, Jesus is actively pursuing the lost: the tax collectors and sinners (Luke 15:1-2; also Mark 2:17; Luke 5:13-32; 19:10). How are they going to realize that they are sinners, and that there is salvation for all who believe, unless someone seeks them out (see Rom 10:14-17)? So, Jesus is making a comparison between himself, the shepherd, and the woman. This goes another level deeper when you realize that the sheep and coin are owned by the shepherd and woman, respectively. Jesus is the Lord of lords and King of kings which makes all of us his possession (Rev 1:5; 17:14). Add to this the fact that God effectually calls his own (Matt 22:14; Jn 6:65; Rom 8:28-30; Eph 1:4-5; 2 Pet 1:3), and suddenly one can see how Jesus is speaking beyond the historical situation of Luke 15:1-2 with these two little parables. These parables speak about how God pursues and rescues his children. But the Parable of the Prodigal Son does not include any kind of pursuing narrative.

The Prodigal Son parable instead pictures a son who has taken his inheritance early, squandered his wealth, and decided to return home of his own accord (Luke 15:11-20). His father never pursues him, although he is overjoyed to see his son finally return (Luke 15:20-24). Sometimes, we have to let someone self-destruct before they realize they were wrong (also 1 Cor 5:5). Does this father-son interaction negate our previous observation about God pursuing his own lost children? No, because the main point of these three parables is that God loves it when someone repents of their sin. The primary goal here is not to reveal to us the hidden workings of God. But the fact that two of the three parables speak of this pursuit should be a guardrail when interpreting The Parable of the Prodigal Son. It would be wrong to conclude that the prodigal son was just smart enough on his own to return to his father. The real-life parallel would then be that only those who are smart enough to repent of their sin do so. This would create a self-righteous theology (of like kind with that of the scribes and Pharisees), in which only the best and smartest people can be God’s children. You are not intrinsically better than someone just because you repented and they did not. That would be the opposite of grace, and if it were true, you would have a reason to boast in yourself (Eph 2:8-9).

So, when we read The Parable of the Prodigal Son, we must remember it is part of a series. It would be silly to only read the third book of a trilogy. You need books one and two for context. This is exactly how Luke 15 works; you need all three parables. The first two parables speak of how God pursues us when we are lost. If we skip right to the third parable, we miss this. And if we skip the third parable, we miss Jesus’ pointed rebuke of the scribes and Pharisees found in the correlation between them and the eldest brother (Luke 15:25-32). Jesus tells three parables in a row with the same basic message – why would we then choose to skip over the first two?

In the next post, we will look at another trilogy of parables, a trilogy about the timing of the Lord’s return.